Forensics Under the Microscope: The FBI and Hair Analysis

/

Ann and I are in the process of switching writing gears from our current Abbott and Lowell series to our new FBI K-9s series. So when a story recently broke that combined the forensics of one series and the organization of the other, it caught our attention. And what a story it turned out to be. We’re going to be starting a new series of blog posts this week as a result: Forensics Under the Microscope—what happens when the science of forensics goes wrong. Needless to say, the ramifications are enormous.

The FBI story concerns their use of hair analysis in criminal investigations and prosecutions. But before we get into that, let’s start with the technical basics—what is hair analysis and how is it used as part of forensics?

What is the structure of a strand of hair? Hair is actually made up of a number of components, but we’re going to look at the main three: the medulla—the middle or marrow of the shaft; the cortex—the thickest part of the shaft which also gives the hair colour; and the cuticle—the scaly outer layer comprised of dead cells.

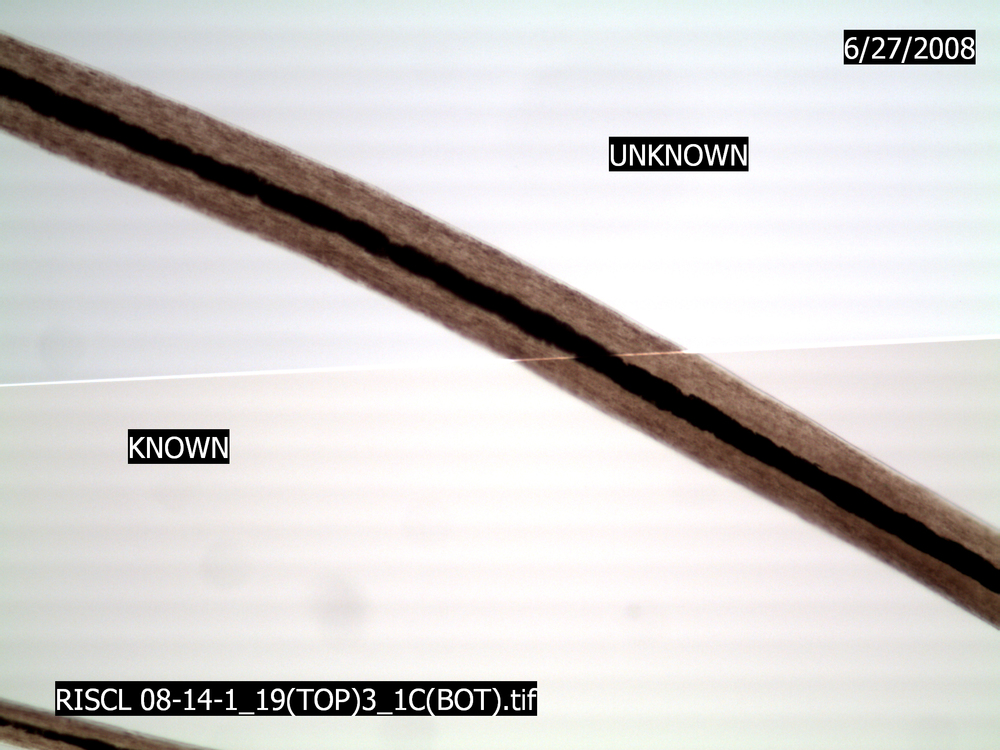

What is compared? When crime techs go through a scene, they collect trace evidence, including hair and fibers. When a suspect is arrested, investigators will take various samples from the suspect, including strands of hair. The hair is first examined macroscopically for colour, coarseness and curliness. It is then examined microscopically at up to four hundred times magnification, and the structure and characteristics of the hair are compared side by side in the same field of vision as hairs found at the crime scene (see above photo).

How is a match made? Microscopically, the crime scene hair and the suspect’s hair are compared to match diameter, characteristics of each structural section, and colour variations. A match upon several criteria may be considered a positive result. But unlike fingerprinting, which in its early days had a set number of points that had to match to be considered a positive result, hair analysis depended more on the analyst’s subjective opinion about colour and texture with no minimum number of matching characteristics. Worse still, two examiners might not come to the same conclusion about a single comparison, but the testifying analyst would still have the final word. Finally, the science of hair analysis came into question since there was very little population-specific data about hair traits—i.e. how often a certain trait could be found at random in the general population. As a result, outrageous probability claims (i.e. a one in a million match) were declared during court testimony with absolutely no supporting data.

What happened at the FBI? It was recently reported that the FBI admitted to twenty years of overstated hair analysis evidence in favour of the prosecution. During the 1980s and 1990s, 26 of 28 analysts from the microscopic hair comparison laboratory gave erroneous statements concerning evidence, often overstating the reliability of the technique and the probability of accurate matches. Out of a possible 2500 cases spanning 46 states during that time period, 268 convictions involved hair analysis. Of those convictions, 257 or over 95% of the cases are affected by these erroneous or exaggerated analyses. Of those 257 convictions, 38 suspects were sentenced to death and 9 of these individuals have already been executed, while 5 more died during incarceration. In addition, 13 crime lab examiners mishandled these cases, often not informing defendants that their convictions might be in question.

Is hair analysis still used today? The FBI recognized more than a decade ago that there were problems inherent in the technique, and stopped using it early in 2000. At the time, FBI Unit Chief Douglas W. Deedrick said that the “experience, training, suitability of known hair standards, and adequacy of equipment” could all affect the reliability of the analysis. Another issue raised was that some analysts considered certain microscopic characteristics so unique in hair samples that if the sample partly matched only on these microscopic characteristics, that would be considered a full positive match. Yet there was no population data to support this opinion.

Some consider fingerprinting to be too subjective and prefer definitive evidence such as DNA identification. Yet hair analysis is even more subjective and, as an identification tool, was compared by Deedrick as being no more useful than the ABO blood matching system. A match might steer the investigation towards a group of people, but it should never identify a specific suspect.

What’s the bigger picture and the result of this reveal? Does this mean that all convictions affected by this flawed analysis will be overturned? Of course not; other evidence in the cases may have been strong enough to have convinced the jury without the additional hair evidence. But every case must be individually re-examined.

It’s a story we’ve seen before and that we’ll look at more closely in the future—departments that are part of, or associated with law enforcement organizations, whose employees feel obligated or are externally pressured to support that organization, despite the actual laboratory findings. For any scientist, this is a horrific thought. As I’ve often told my graduate students, your results are your results; they’re not wrong, they simply are. And you shouldn’t bend them to fit your hypothesis. If they don’t fit, then your hypothesis is wrong.

The larger picture here is not scientific results per se, but rather their downstream effect and the lives changed, often forever, because of them. For those looking for more specific information, the Washington Post has published a detailed breakdown of the cases involved.

The U.S. federal government has made the decision to waive the statute of limitations in all of the involved cases and will do DNA testing (not available at the time) in the hopes of conclusively confirming or overturning the convictions. For many involved, it’s much too little, much too late. But hopefully for some, it will be a chance to try to pick up the lives stolen from them so many years ago.

Photo credit: University of Rhode Island

Coming up on Saturday, May 2nd, it’s the inaugural Canadian Authors for Indies Day! I will be appearing on Saturday at 4:30pm at A Different Drummer Books in Burlington, ON (address below) with a roster of very talented authors. So if you’re in the area and would like to stop by and show a great indie bookstore how much we still need them and how important they are in our community, I’d love to see you that day. And if you’re not local to me, but still want to show your supports, please stop by one of the participating indie bookshops listed on the website!

COMPLETE!

COMPLETE! Planning

Planning