Forensic Case Files: The Exhumation of H.H. Holmes

/We’re ramping up toward the release of Abbott and Lowell Forensic Mysteries #5, LAMENT THE COMMON BONES, so I thought it would be fun to do a forensic anthropology story this week. There was a big story last month that I didn’t review because we were busy with the launch of BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE, but it’s worth covering—the exhumation and the analysis of the body buried in the grave belonging to H.H. Holmes.

For anyone unfamiliar with Dr. Henry Howard (H.H) Holmes, he was a serial killer and con artist who operated against the backdrop of the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Holmes, an alias of Herman Webster Mudgett, was born in New Hampshire in 1861, graduated from the University of Michigan’s Department of Medicine and Surgery in 1884, and was a bigamist, at one point being married to three women simultaneously while being engaged to several others.

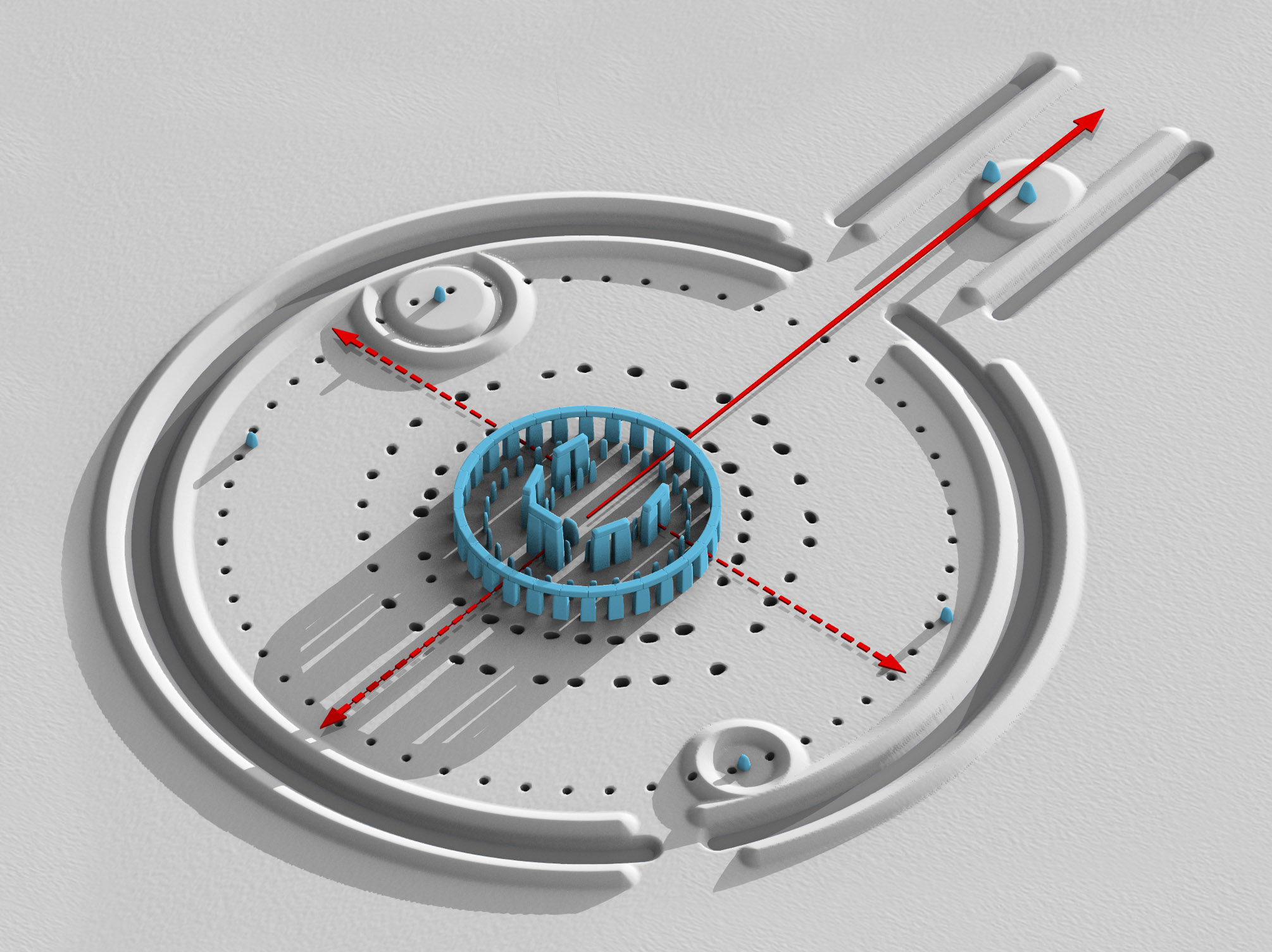

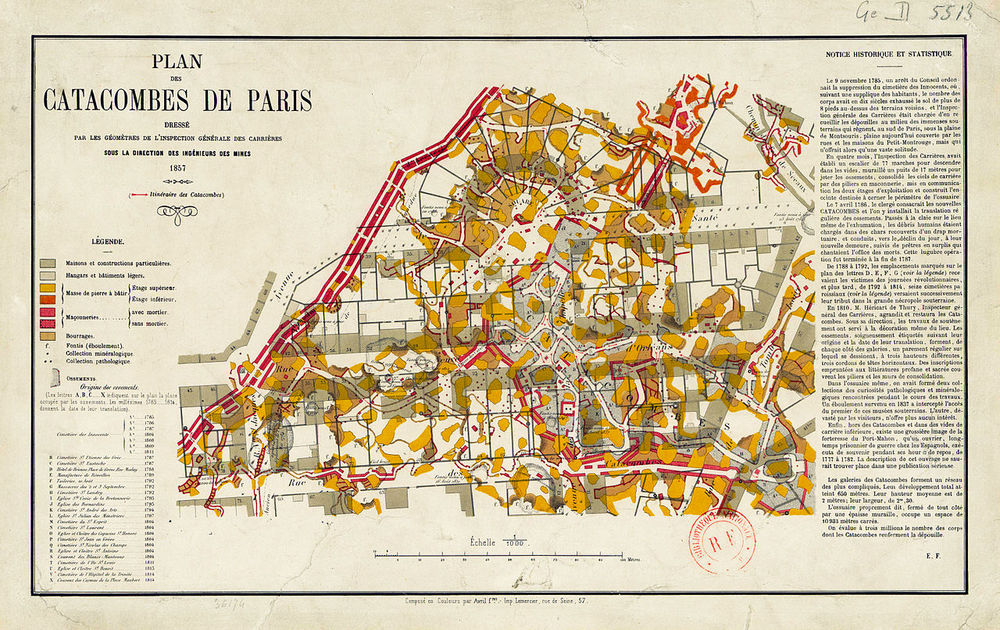

Holmes settled in Chicago in 1886 and purchased a drug store on a busy intersection in the Englewood neighbourhood. He purchased a lot on the opposite corner from the drug store, designed, and then started construction of a multi-use, three-story building—a drug store on the ground floor with apartments and hotel rooms above that he claimed were part of the World’s Fair Hotel (though there is no evidence they were ever used for this purpose, or even fully completed). His own rooms were located on the third floor.

The upper floors of the building were a nightmarish design of soundproofed rooms, labyrinthine corridors, doors that locked only from the outside, air-tight spaces with installed gas vents, and chutes that transported room occupants to the basement for incineration or to be dissolved in vats of acid. Holmes was ingenious in his methods, even ensuring that no single builder understood the depravity of the building’s design—he would fire workers after short contacts, ensuring that no one ever fully understood the full horror of his plans.

Following the discovery of the building’s real purpose, it was christened ‘The Murder Castle’—a place where people went in, but never came out. Holmes himself admitted to killing twenty-seven individuals, though only nine deaths were confirmed. However, his legend has grown, and some accounts report over two hundred deaths at his hands. What is certain is that several of his paramours/fiancées lost their lives inside the Castle, as well as a number of women who responded to advertisements for employment.

Apart from the lives lost in 1893 during the World’s Fair, it was actually the death of a fellow con artist that finally convicted Holmes. The pair concocted a scheme to fake the death of an inventor in a laboratory explosion and fire. Benjamin Pitezel set up the fake persona and purchased a $10,000 insurance policy. Holmes was supposed to produce a body to be disfigured during the fire, but, instead, he killed Pitezel so he could make the insurance claim without having to split it with a partner. Holmes was eventually caught, tried for Pitezel’s murder, and sentenced to death. He was hanged in 1896.

Earlier this year, a request was made by the Mudgett family to exhume Holmes’s grave to ensure he was buried there. Family legend told that despite Holmes’s request to be buried in a coffin filled with cement and then interred under seven three-thousand-pound barrels of cement to deter grave robbers and infamy seekers, he had escaped execution. The exhumation order was granted and the body was recovered last spring.

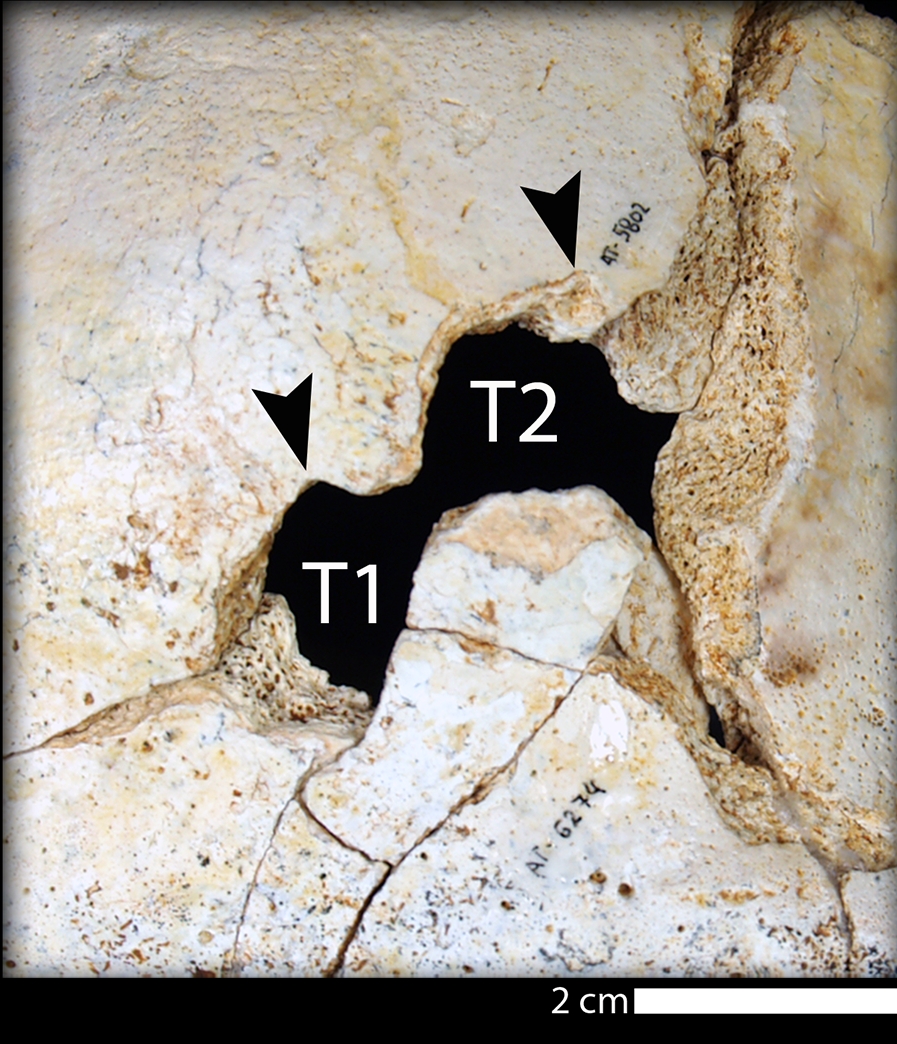

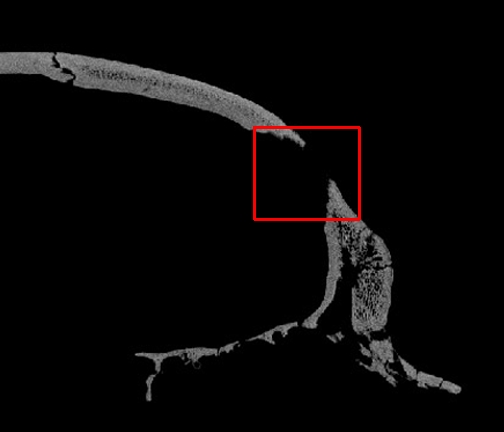

Samantha Cox, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, completed the examination. Due to the method of burial within cement, the body had not fully decomposed. The man’s burial clothes were intact and he still sported a mustache, but the tissues were mostly putrefied but not fully liquefied. Due to the extent of decomposition, DNA could not be extracted from the remaining tissue slurry, but was instead extracted from tooth pulp for PCR and familial DNA profiling. Last month, the results were revealed: the body in the grave of H.H. Holmes was indeed Holmes himself. Despite his wily ways and life of crime, in the end, he was caught and punished. Holmes body was returned to his grave and buried once again.

As a side note, anyone who is interested in more on the life of H.H. Holmes would enjoy the narrative non-fiction novel ‘The Devil in the White City’ by Erik Larson. It’s a well-researched, fascinating account of both the 1893 World’s Fair ‘Columbian Exposition’ and the simultaneous, horrific career of H.H. Holmes.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

COMPLETE!

COMPLETE! Planning

Planning